Pressure, it’s rarely a comfortable state for anyone, let alone elite athletes. So how do we train our athletes in preparation for dealing with it? We explore findings from a 2022 research study titled ‘The Role and Creation of Pressure in Training’ and discuss the strategies and tools Athlete Assessments’ Founder and 4x Olympian Bo Hanson has found to be most effective for pressure training implementation.

Performance pressure is underpinned by self-awareness

Conducted through the lens of sport psychology, ‘The Role and Creation of Pressure in Training’ research study, explores techniques of pressure training and how these can be utilized to improve performance in competition. Research findings were formulated from semi-structured interviews with eight sport psychologists and eight international-level athletes, with the aim of uncovering their views on pressure training, effective methods, and mechanisms for improving overall performance.

One of the core research findings was that preparation for performance pressure is underpinned by awareness of individual stressors and the implementation of coping skills required to overcome them. The study highlights the importance of coaches learning the specific and individual stresses affecting their athlete’s performances. This way, effective strategies and coping regimes can be implemented to better facilitate pressure practice.

While there are many conceptualizations of what pressure is, the research’s authors, William R. Low, Paul Freeman, Joanne Butt, Mike Stoker, and Ian Maynard stated,

“An individual’s level of stress depends on one’s appraisal of the current situation and individual differences mean that any given event cannot be assumed to be a ‘stressor’ for everyone.”

Sound familiar? It does to us!

If you’ve read our work before, you’ll know we talk about the importance of understanding the individual nature of your athletes as a critical element for achieving performance, whether you’re a coach or a Sport Psychologist working with them. To do so, we look through the lens of our Athlete Assessments DISC Profiles, which utilize a simple four-quadrant model to measure degrees of behavior in any individual. These results form a vital part of any athlete-centered coaching approach, as understanding the differences and needs of our athletes, allows us to formulate the most effective approach to working with them.

Every individual has a pace preference

Everybody, regardless of their DISC Profile, has a preference for the pace at which they act, process, and make decisions. Typically, people who score highly in the decisive and task--orientated Dominance ‘D’ style, are faster-paced, as are the high energy, spontaneous, and creative Influence ‘I’ style. Those who score highly in the other two quadrants prefer a slower-pace. The Steady ‘S’ profile will have a relationship focus, and will contemplate the feelings of those around them, to ensure everyone is on-board and comfortable with the task or situation. People who score highly in the Conscientious ‘C’ quadrant can be relied on to get the details right. In sport, they’re usually the ones who know all the rules and have refined the logistics of a set play to a tee.

So how does this relate to stress and pressure?

Pace is one of the primary influences on everything we do, and is also one of the principal differentiators between individuals, and more specifically, athletes.

When approaching an important event or competition, our athletes are likely to experience mixed feelings and emotions surrounding performance and perhaps, uncertainty of outcome. Athletes may feel spectator nerves, or the fear of media scrutiny. Others however, may thrive in these uncomfortable conditions. Any number of circumstances can weigh on athletes during and prior to performance. The only thing we can be sure of as coaches, is that by recognizing and understanding the stressors our athletes experience, we can implement better management and preparation practices. As one sport psychologist interviewed shared,

“You need to deeply understand where the individual goes to under stress, what stress and pressure looks like for that individual, and then [begin] capacity building to manage that response.”

When designing pressure training structures, it’s important for practitioners or coaches to collaborate their athletes to identify the most relevant aspects of a competitive environment that a particular athlete finds most stressful. Once these elements have been identified, they can be used to create scenarios which approximate those pressures of actual competition. When simulating pressure at training, often coaches will resort to standard practices, such as increasing the severity of consequences, or difficulty of a task.

Interestingly, these methods were not found to be consistently effective. The research found,

“Demands that increase difficulty often do not increase pressure. Athletes may perform worse, but not feel pressure if they do not have more reason than usual to maintain performance. Coaches and practitioners should not assume that a consequence will create pressure just because it is unpleasant to athletes.”

Step 1: Identify individual stressors

If a situation requires an athlete to act outside of their natural behavioral preferences, it may cause them stress and create pressure. Remember, natural or preferred behavior is the way we act without thinking and when we are in a comfortable state. By understanding an athlete’s natural or preferred behavior, we can easily identify these potential stressors. Stretching or flexing our behaviors to better suit a certain situation is known as adapting, and through increasing our awareness of our natural behaviors, we can increase our ability to make changes in our behaviors when necessary.

For example, if an event has a detailed pre-competition check-in or registration procedure, this will likely challenge the ‘D’ and ‘I’ styles because in their speed they are prone to missing details. The act of slowing down to pay closer attention may be taxing for them, but if they are aware of this prior to the moment, they can at least be prepared to make the necessary adaptations. In contrast, if an athlete of a slower-paced style, ‘S’ or ‘C,’ is competing against an opponent who forces them to compete, react, and make decisions at a faster-pace, this is going to create challenge and potential stress for them. Acting in a non-preferred way can be done successfully but will take energy and conscious effort. Naturally, adaptations can be made and challenges as such can be overcome but it’s important to skill your athletes to implement strategies to allow it to occur. Bo shared one of the many evaluative strategies he often uses is asking a team or athlete, ‘What does the sport demand and what does the role you play demand?’

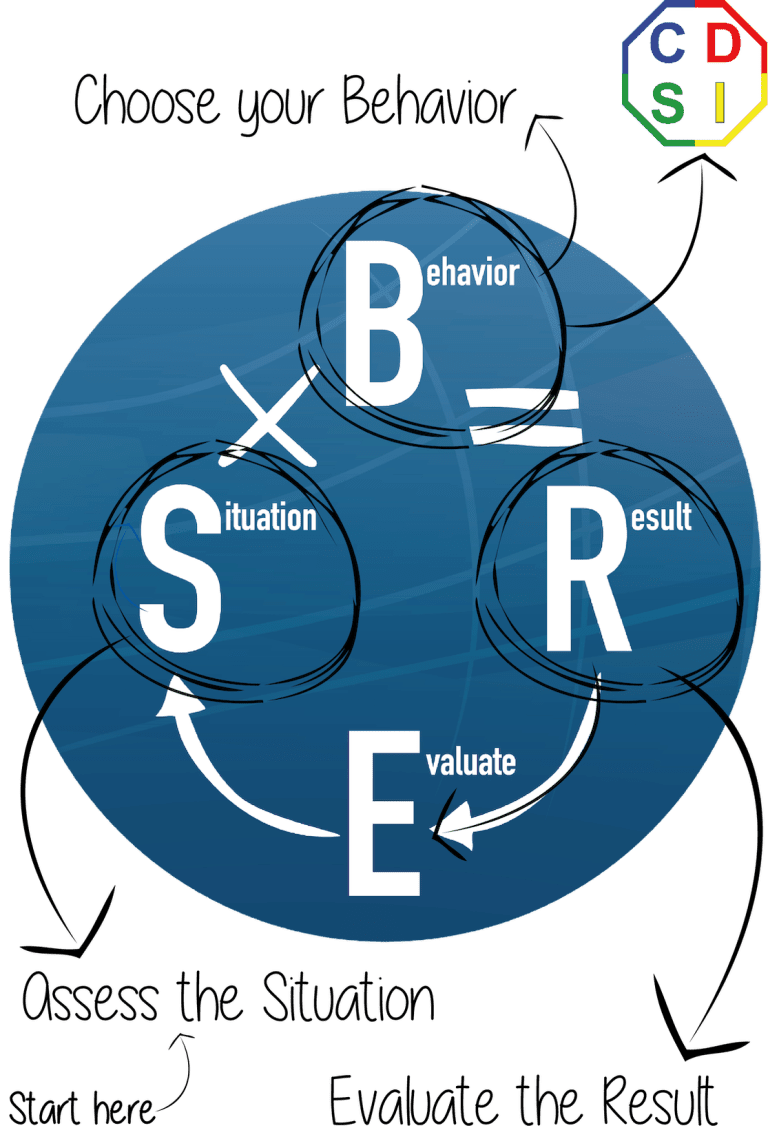

The question is associated with the SBR Model, which is commonly used by Bo when working with teams. It encourages athletes to first assess a Situation, before choosing the Behavior (here’s where the adaptation may come into play) that will give them the best Result, then Evaluate the Result and learn from the interaction.

The AthleteDISC Profile is also an effective way to delve deeper into understanding an athlete’s natural behavior. The 40-page report outlines the individual athlete’s unique spread of strengths, their preferred pace, style of communicating, how they approach tasks, and build relationships with the people around them. A component of the AthleteDISC Profile also provides insights into an individual’s likely characteristics and needs when under stress.

Step 2: Develop a coping strategy

Knowing which elements of an environment challenge and trigger the stress of our athletes, enables us to strategically develop a plan tailored to individual and team needs to overcome such obstacles, without detriment to performance or long-term goals. This is referred to as a coping strategy. In the research study, the sport psychologists and athletes reported that pressure training helped athletes to develop coping skills to manage their anxiety, attention, and self-talk when under pressure. One athlete noted,

“If I’m better at understanding pressure and navigating those thoughts quicker, it means I don’t get as much of a physiological response.”

The study outlined how pressure training helps to increase athletes’ self-awareness of their responses to pressure. It highlighted tendencies under pressure that were less evident when training was not pressurized, stating,

“Another advantage of pressure training was that the pressure prompted athletes to practice their coping strategies while training their sport. Merely discussing self-talk or emotion regulation was not necessarily sufficient for athletes to apply strategies under pressure in competition. Practicing these strategies under pressure allowed athletes to develop them into reliable skills that they know how and when to use. Without pressure in training, competition might be the only time athletes would find themselves having to learn how to cope.”

By utilizing a tool like the AthleteDISC Profile which details an individual’s specific stressors, coaches and sport psychologist can apply the stress management and communication recommendations outlined on this page. By doing so they are able to create a tailored pressure environment for athletes to formulate effective coping strategies when they need it most.

Ultimately, a coping strategy will look different for each athlete, so it’s worth highlighting the importance of exercising the coach-athlete relationship to approach this together. After having the athletes complete their AthleteDISC Profile, coaches or sport psychologists can facilitate regular one-on-one discussions around their individual stress triggers, then what works for them and what doesn’t, in terms of managing them, to enable personalized coping strategies to be formulated, measured, and evaluated. Using the AthleteDISC Profile as a tool to navigate such discussions can be extremely beneficial in not only having an individualized approach to each athlete, but also in creating a safe and neutral language for the conversation to take place in.

Step 3: Encourage athletes to change their relationship with pressure

Consider for a moment the two-fold impact of a particular pressure on an athlete; there is the impact of the pressure itself, and then there is the damage that reactions to this pressure cause to the athlete’s performance. These impacts form an athlete’s relationship with pressure.

While the research concluded that with systematic training to identify pressures, develop coping strategies, and practice them in simulated competition scenarios, athletes were unlikely to feel any less pressure or anxiety about performing. It did however note that the athletes were able to understand that by changing their relationship with pressure, they could optimize their performance and achieve better outcomes.

“Pressure training seems to provide athletes with evidence that they have already coped with challenging tactical situations and pressure-induced anxiety, and such mastery experiences can be a primary source of self-efficacy.”

Athletes are expected to practice their technical skills to improve their on-field performance, but developing their ability to perform those skills under pressure should be no different. Previously, research has recommended coaches and practitioners reduce athlete stress by reducing the presence of things that cause stress in the lead up to an athlete’s performance. However, what we can see is that tailored pressure training, done so within a controlled and safe environment, can be used to intensify elements of a potential situation and prepare the athletes to be pushed out of their natural tendencies. Through this practice, when athletes encounter a similar situation during competition, they will be well equipped to identify the stressor and adapt to overcome the challenge.

Step 4: Practice momentary behavioral adaptations

Athlete Assessments’ DISC Profiles are not built on binary absolutes, and so, everyone will have a percentage of each style in their profile. Whilst this percentage may be as small as 2%, an individual still has access to the behavioral characteristics of that profile and therefore, can adapt to implement them to some degree if required. For example, as mentioned earlier, someone who is high in ‘D’ might measure low in ‘C,’ meaning they do not easily attend to details. However, if they have an understanding of ‘C’ characteristics and how to apply them, they have the capability to perform in a way that a ‘C’ does for a period of time. If someone is a midrange ‘D’ (40-60), their ‘D’ characteristics are not weaker, just less prevalent in their behaviors or put into action less often.

Having even a small amount of other, non-preferred styles in our profile means we can authentically rely on this behavior when we need to. We may need to stretch it or increase the number of times and the duration of time that we perform different behavior, but by practicing our ability to adapt and the speed at which we can do so, the more successful we are going to be in a diverse range of situations.

Encouraging athletes to contemplate their own DISC Profile regularly to understand their preferred methods of behavior, and where they may need to temporarily ‘flex’ both on and off ‘the field’, can assist in learning how adaptations be practiced to better cope with pressure. For example, there may be situations where an athlete needs to interact with a team member who has a different DISC Profile to them, or step in and lead a team through a play that requires a different set of behaviors to what they are used to.

Similarly, there will be occasions during performance or competition that demand a momentary adaptation from an athlete. Perhaps a high ‘C’ needs to adapt to react at a faster-pace, or a high ‘I’ needs to better analyze an opponent’s play, rather than being purely reactive. To further expand your knowledge on the effect of adaptations, access our article on Momentary Vs Sustained Adaptations.

Feelings of pressure are inevitable for athletes competing at any level, and so it’s imperative to implement the right strategies to train, prepare, and manage pressure itself. Pressure training has proven to be one of the most effective approaches in equipping athletes with the skills to cope with stressful scenarios. Ultimately, pressure training itself should take place in an environment that balances challenges of pressure with support and education from sport psychologists, coaches, and staff.

With the research insights gathered, these are just some of the tool and strategies that coaches and sport psychologists can implement to better manage aspects of pressure training. Use this as a guide to help you on your way to successfully integrate effective pressure strategies within a team to optimize performance, and ultimately, win more often. Essentially, the most successful athletes are those who can adapt their behaviors when it matters most and through this approach to pressure, a positive culture and relationship with it can be achieved.

To delve deeper into the practice of pressure training, access the full research study, The Role and Creation of Pressure in Training.

Where to from here?

Providing athletes with strategies to recognize and adapt to pressure is one way to ensure optimal performance. To maintain performance and resilience however, the application of mental skills to build athlete ‘toughness’ is just as important. Are your athletes, athlete tough? Access the Athlete Assessments ATHLETE TOUGH™ program for resources and insights into maximizing the mentality of your athletes.

Recommended Articles

This article was initiated by an important question that one of the gymnastic coaches we work with asked, “How can we make sure we’re ready to perform at our very best the moment competition begins.”

very athlete has a way of doing things that just feels right. A way they like to shoot, or move, or run. Like writing with your dominant hand, it’s comfortable and not in any way forced. That’s what a ‘natural profile’ or ‘natural style’ in the AthleteDISC Profile is, it’s the way you prefer to do things.

When an athlete is able to compete according to this natural style, rather than continually making significant adaptations, they perform at their best. They’re not using any extra energy to do something that doesn’t come naturally.

How many times have you witnessed the heartbreak of an athlete faltering at a crucial moment? The painstaking drama of the moment can be excruciating to watch, particularly when the athlete is at the height of their career or even worse, an athlete you coach. At these times, the terms choking or panicking are thrown around loosely to label the under-performance of the individual or team. But what do these terms mean? Is there a difference between them? And can anything prevent an athlete from choking?