Recently Sports Illustrated published an important article titled, ‘Is the era of abusive college coaches finally coming to an end?’. The article highlighted alarming issues with modern collegiate athletics based on surveys of 20,000 college athletes, as well as the latest research in psychophysiology, psychology, depression, health and abusive leadership.

In reading the article, what becomes crystal clear is the impact the coach has on either magnifying or eliminating these issues. When we constantly talk about the critical nature of the coach’s role in a young person’s life, it appears this message is only gaining in acceptance and the appreciation of the wider damage a coach can do to their athletes.

It is our hope that when you read this article’s key findings, that you pay attention to the care you give to athlete welfare, issues of depression, the importance of the coach-athlete relationship and the impact of abusive coaches on athletes. It should also be noted that although this research is conducted on college athletes, we would be naive to think these issues do not flow into every other level of sport be it high school, club and professional.

Unsupportive Coaches

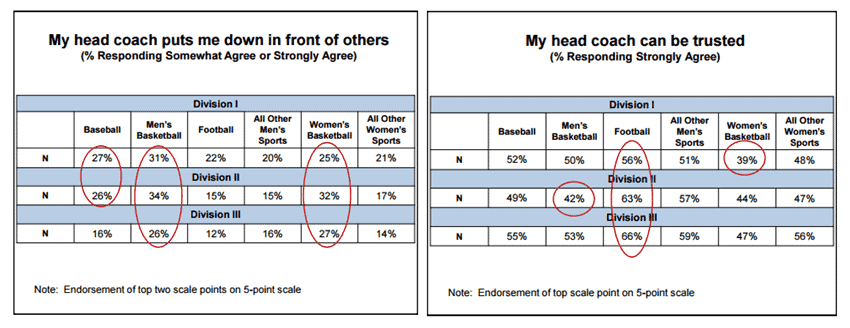

NCAA GOALS Study: In 2010, the NCAA gathered data from almost 20,000 college athletes.

In Division I, 31% of men’s basketball players and 22% of football players reported that a coach “puts me down in front of others,” according to the GOALS study, and only 39% of women’s basketball players strongly agreed that “my head coach can be trusted.”

Overwhelmed, Anxious, and Depressed

An assessment by the American College Health Association (ACHA) of almost 54,000 undergraduates, 7.5% of the varsity athletes found:

- 41% of male athletes had “felt so depressed that it was difficult to function”

- 52% of male athletes had “felt overwhelming anxiety”

- 45% of female athletes had “felt so depressed that it was difficult to function”

- 59% of female athletes had “felt overwhelming anxiety”

- 14% of athletes said they had “seriously considered suicide”

- 6% of athletes had attempted suicide.

A 2013 study by Georgetown University Medical Center asked 117 current and 163 former Division One athletes if they suffered from depression.

“Researchers expected the ex-athletes to be most susceptible [to depression], as they navigated the transition from the spotlight. Instead, the study found depression to be more than twice as common among active athletes than those who had finished their college careers.

Negative vs. Positive Emotions

Dr. Barbara Fredrickson is the author of Positivity and a social psychologist who runs the Positive Emotions and Psychophysiology (PEP) Lab at North Carolina.

“Negative emotions grab people’s attention more,” says Fredrickson, who attributes this to evolutionary reasons, because survival in the prehistoric environment often depended on sudden alerts. “So there’s a perception that the best way to get what you want out of employees or players is by negativity or threats, or being stressful or intense. But in terms of bonding, loyalty, commitment to a team or a group and personal development over time, negativity doesn’t work as well as positivity.”

Fredrickson’s research shows that positive emotions expand awareness, allowing for reception of a broader array of information. They make people more flexible, resilient and creative. A college age athlete can be highly susceptible to the influence of coaches, parents and peers, and may not have fully developed what she calls “resilient emotional regulation,” so abuse may leave a deeper scar on a young adult than an older one.

Two of her findings speak directly to the player-coach relationship. “Positive emotions are especially contagious,” she says, “and a leader’s positive emotions are more contagious than anyone else’s.”

Her other insight comes as a result of eye-tracking analysis, brain imaging and behavioral studies, which together show that improved mood actually broadens the perceptual field. “People’s peripheral vision expands,” she says, “when they’re experiencing positive emotions.”

In other words, by yelling at his point guard for missing that wide-open teammate in the corner, a coach has probably ensured that it will happen again.

Athlete’s Brains are still in Development

Dr. Richard Davidson directs the Center for Investigating Healthy Minds at Wisconsin.

“The brain is a work in progress, constantly shaped by the experiences around us. But the brains of young adults are particularly malleable. If young people tend to make unwise choices, it’s partly because the prefrontal cortex isn’t fully developed until after age 25. Meanwhile adversity and stress can impair neurogenesis, the process by which that ever-evolving brain produces new cells.

According to Dr. Richard Davidson, “there’s some evidence to suggest that stress can impair the circuitry that regulates negative emotions in particular. So [abuse] can have this very pernicious effect, which can have a spiraling effect and lead to an increase in negative emotions as a consequence.”

Abusive Leadership in Sport

Dr. Ben Tepper, from Ohio State’s Fisher College of Business has made abusive leadership in the workplace his specialty. He has studied industries such as manufacturing, health care, financial services, education and the military. The NCAA used his Abusive Supervision Scale (the Tepper Scale) in its GOALS report.

Believing that the coach-athlete relationship is essentially a boss-employee arrangement by another name, Tepper overlaid GOALS results on to his own vocation-by-vocation data.What he saw left him slackjawed:

Abusive leadership is two to three times as prevalent in college sports as in the orthodox workplace.

When he studies an industry, Tepper identifies what he calls “precursors in the environment” that make abuse more likely. “They’re all in sharp relief in college coaching,” he says. “Bosses under stress combined with targets who are weak and vulnerable and can’t fight back. Talent can give you some power, but it’s not like you can just say, ‘I’m leaving,’ because you have to sit out a year. The only protection an athlete has is to be an amazing performer.”

You can watch Dr. Ben Tepper compare his own data on abusive leadership in other industries with the NCAA’s data on abusive leadership carried out by college coaches here:

“Our conviction that hostility works is encouraged by a culture that makes legendary figures of Knight and Steve Jobs. Tepper believes that both succeeded in spite of their abusive leadership—that Knight was very tactically smart, and Jobs had a rare combination of design sense and business acumen.”

“The studies all say there’s no incremental benefit to being hostile,” he says. “Even when you control for a leader’s experience and expertise, hostility always produces diminishing returns.”

The work of Tepper and others subverts more assumptions. Doesn’t a coach who yells convey urgency that helps players muster strength? In fact, he says, abuse is depleting:

“We all have a finite amount of energy. You’re concerned with whether your coach will yell at you rather than doing your job, so it impairs your executive function. And bosses who combine hostility with support are more depleting, because you don’t know what’s coming next.”

Doesn’t a hostile coach create team cohesion? In fact, she’s more likely to create fault lines and cliques, which can lead to a downward spiral. “If you’re angered by your environment, it’s harder to come together with others in that environment,” Tepper says.

Sources:

- http://www.si.com/college-basketball/2015/09/29/end-abusive-coaches-college-football-basketball

- http://www.ncaa.org/sites/default/files/Goals10_score96_final_convention2011_public_version_01_13_11.pdf

- http://explore.georgetown.edu/news/?ID=69971

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3658399/

At Athlete Assessments, we’re here to provide you with excellence in service and to help you be your best. If there is anything we can assist you with, please Contact Us.

Recommended Articles

The coach-athlete relationship, a research backed non-negotiable when it comes to getting the best and sustained performance out of your athletes.

The skill of decision making is closely linked to problem solving. For some athletes, making the right decisions at the right time is a well-developed skill, whilst other athletes find this process more challenging. Like any critical skill, the key to developing an individual’s decision making is to practice. So, where should an athlete practice their decision making? The answer is in training.

As a coach ensuring your athlete is always striving to gain a 1% improvement in their performance can be one of the hardest parts of your job. At Athlete Assessments, we often speak about the importance of a quality coach-athlete relationship, and how this can be used to improve athlete performance. This article discusses how to improve emotional bonds and engagement, and how understanding these factors improves your athlete’s performance.

Compiled by Liz Masen, CEO of Athlete Assessments, the Coach Survey Summary Results. What are the top three sports coaching challenges faced?